Blackjack odds are as good as you’ll get at most casinos. In most cases, the casino has just a 1% edge versus the gambler. So in a given night, you can go on a great run and win a lot of money playing blackjack. But of course if you played every day, all day, your odds of a sustained run steadily decline and approach zero. Active investors should try to be the house (value), but many will always be gamblers (growth).

Quick reminders on value and growth. I define value as the cheapest 10% of U.S. stocks and growth as the 10% most expensive U.S. stocks. In the average 12 month period, value outperforms the equal-weighted market return by 5.6% (and its somewhat consistent: value has a 76% win rate). A long-term value investor of this type has obviously been hugely successful. Growth is pretty much the inverse. Average annual underperformance of -6.8%, and a 73% lose rate.

But here is the interesting part. The “edge” for our value investor is pretty similar to that of the casino. Within that cheap value portfolio which does so well on average and over time, just 53% of the stocks beat the equal-weighted market return. These winners outperform by an average of 29.2%, but 47% are still losers. Growth looks very different. Within the expensive growth portfolio just 34% of the stocks beat the equal-weighted market return. This 34% outperforms by a much higher average of 48.9% (as compared to the 29.2% for the value “winners”).

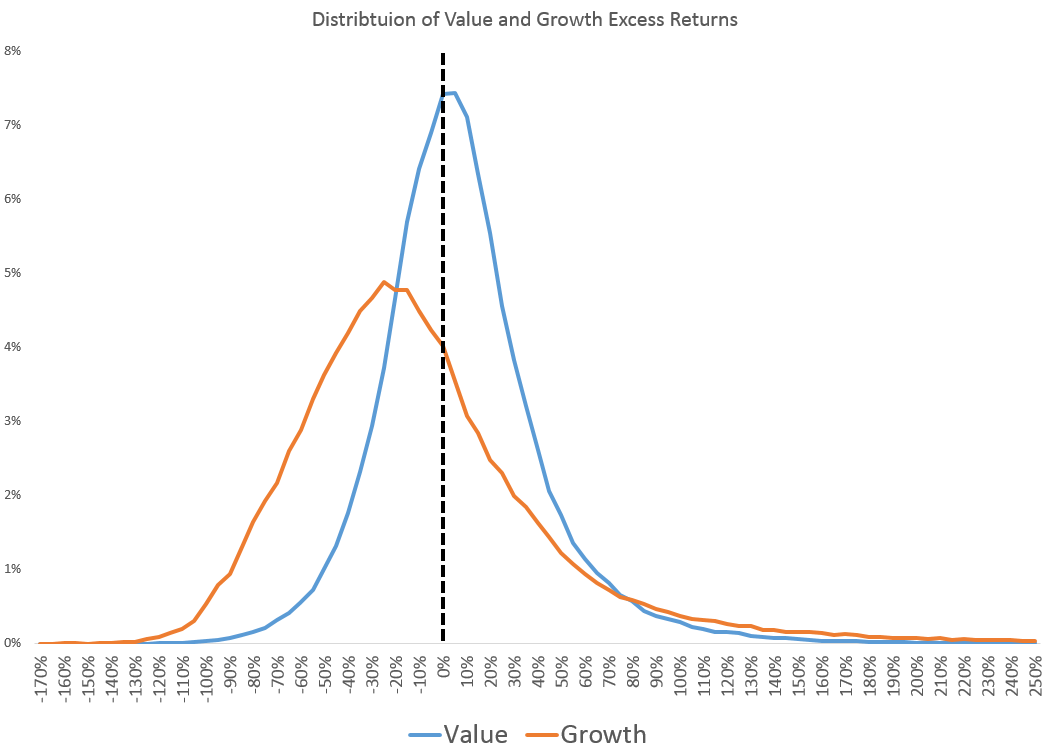

Notice this contrast between value and growth very clearly in the below distribution. 34% of the growth curve and 53% of the value curve lie to the right of the 0% line (positive excess returns). Growth has the more significant tail (more growth stocks deliver ridiculous excess returns), but the overall odds for value are much better.

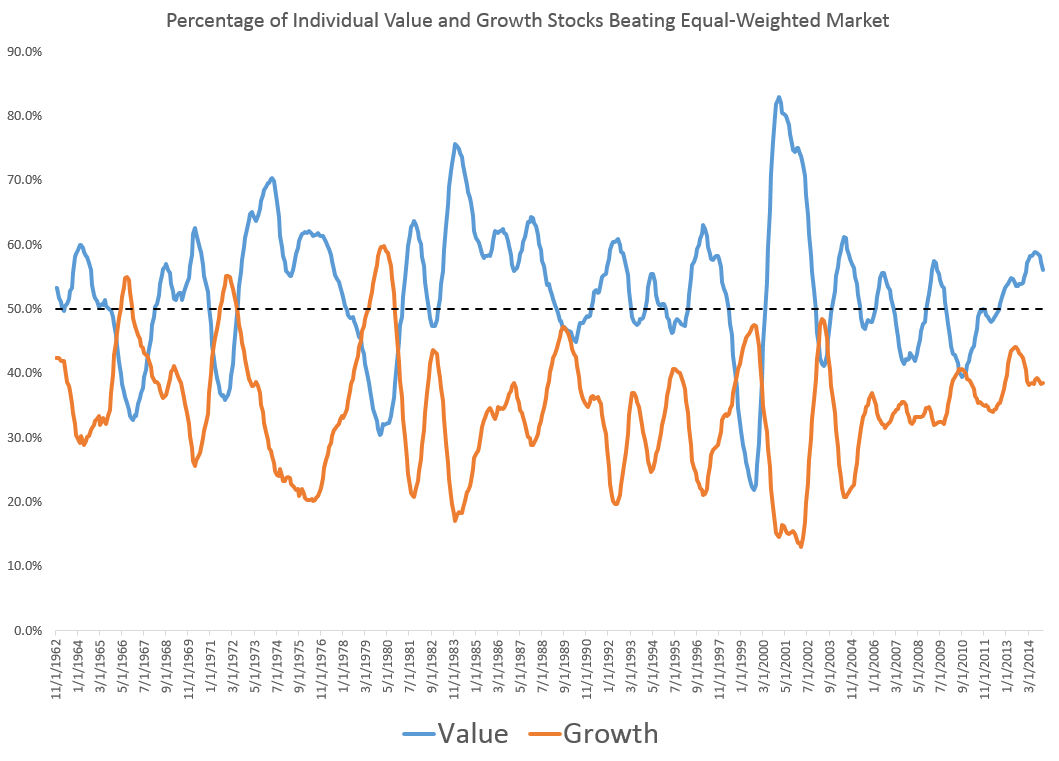

Of course, this isn’t some universal truth. It bounces around. Here is a time series (smoothed) of the percentage of individual value and growth stocks beating the market.

Just like the house in a casino, value investors sometimes get destroyed. Several very high profile investors with great long term track records felt that pain in 2015. Real value stocks (and strategies) hurt to buy and sometimes really hurt to hold.

This great research report from Kaleidoscope Capital puts this idea of good odds with occasionally acute pain well:

This profile of small gains followed by the occasional large loss looks awfully similar to that of writing insurance. The insurance underwriter safely collects a monthly premium until the hurricane blows through, resulting in large losses. Similarly, selling stock market insurance through put options earns consistent returns until a 1987- or 2008-style market crash strikes. While value investors rarely traffic in actual options, one has to wonder if there is something about their strategy that intrinsically results in this short option profile.

Value investing (historically) is like selling insurance, like writing puts, like being the house. In each of these examples, the key is turning a small advantage on each individual bet into a huge advantage across a large number of bets over a long period of time.

These systems only work with tremendous discipline. An actuary would never change his pricing for a fat 50-year old smoker just because the guy tells an emotional and convincing story about how he will turn his life around and get healthy.

With more people aware of these odds than ever before, the magnitude of the “edge” is an open question for the future. Not everyone can open a casino and be the house, you need gamblers too. But even a reduced edged, paired with steel discipline, can grow to a huge advantage over an investing lifetime.

/rating_on.png)

/rating_half.png)

This distribution would allow one to apply Kelly approach to define the optimal allocation to the value portfolio. The growth portfolio should get nothing…

I like the analogy. To take it even further, the 1% edge that casinos have in blackjack is increased significantly when you factor in the psychological behavior of the gamblers. Most players won’t stop when they’re ahead. They play until their money is gone…and often buy back in.

The house doesn’t have to worry about making emotional decisions. The same is true in the stock market. Investors who have the discipline to stick with strict buy and sell rules have a huge advantage over time.

Thanks for your great blog!

Thanks Patrick - I really enjoy your writing. I totally agree with your broad conclusion on the need for steely discipline and making the most of your edge.

But I wonder if the analogy between value/growth and casino/gambler doesn’t totally hold true. Timing of profits and losses for a casino are random (independent of each other) and the casino employs a buy and hold strategy by being open every day. Profits for a value strategy are somewhat dependent on the relative value of the stocks you’re buying compared with history - so timing of profits from a value strategy are more predictable. A value strategy was a great idea in 2000 but hasn’t done so well vs growth since 2005. So steely discipline doesn’t always equate to sticking with a value strategy under all market conditions. Unlike a casino, a value investor can choose when to open for business.

No doubt there is much more nuance to value. But while your point about value under performing since 2005 may be true for something big and book/price based like Russell style indexes, but the value factor that I used for this post has outperformed handily in that period. Also, I am not convinced that the relative “value of value” is an actionable strategy. I’ve run it many ways and I haven’t found something convincing that you can “time” factors. Again, it might work better for timing Russell Value vs Growth, but that isn’t how I invest.

Thanks for your thoughts!

I need to spend some time with the Kelly approach. I’ve read about it but never implemented it…one problem is estimating the inputs…gets very tricky

How about switching between value and momentum according to performance?

As in: http://blog.alphaarchitect.com/2014/08/28/can-high-minus-low-hml-time-value-and-momentum/

It’s P/B based again but wonder if it would work with a composite value measure and a better momentum factor than 2-12. Works best on smaller caps than large and in concentrated portfolios.